The QuickPAD Pro comes with a text editor and it runs DOS text mode programs fairly well. That means that scripting languages like Awk and Perl can be used to create custom text-based database applications.

This page contains a set of sample Awk scripts to manage different kinds of databases. In all cases, we'll use edit.exe to create and edit the data files, and Awk scripts will be used to query and manipulate the data.

OK, so it's not a fancy GUI-based system, but this method is flexible and the scripts execute relatively quickly. Also, your data won't be locked in some company's proprietary binary file format. There is also the benefit of portability: If your PC can run DOS, you can also run these scripts on your PC. Awk is also available on Linux and on other operating systems.

This page assumes that you are already familiar with database terms like 'record', 'field', and 'search keyword'.

Awk is an interpreted programming language that is designed for managing and converting data files and generating reports from the data.

Awk will automatically read an input file and parse it into records and fields, one record at a time. A typicall Awk script will then manipulate the fields using predefined variables like $1 (the first field), $2 (the second field), etc.

To use Awk, you create an Awk script, and then run it with the Awk program (gawk.exe in this case). Many Awk scripts are small, and it lends itself to writing "one-time use" programs.

All the files on this page are available in the ZIP archive available at this link. Feel free to reuse and customize them.

You will need the GNU Awk program gawk.exe to be installed on your QuickPAD Pro. See the programming page for instructions on installing GNU Awk.

Here is the general format of a gawk command line:

gawk -f SCRIPT DATAFILEwhere SCRIPT is the name of the file that contains the Awk script and DATAFILE is the name of the text file that contains the input data.

That command line will not modify the input file and all the output will be directed to the screen.

If a script creates a new data file (for example, a sort script), the command line will be:

gawk -f SCRIPT DATAFILE > NEWFILEwhere NEWFILE is the name of the new data file that will be created.

If you use a particular script often and get tired of typing in a long command line, you can create a batch file to execute the long command line for you.

Since we are using edit.exe for our data files, it means that we are currently limited to 64K files for our data. We can work around this restriction by using the chop utility program that is described in the software page.

In this section we demonstrate some Awk scripts to manage "index cards" of information. This type of database can be used for any type of simple text lists, like lists of books, music CDs, recipes, quotations, etc.

Our information will be stored into 'cards'. Each card will have a 'title' and a 'body':

Title of Card ------------------------- Free-formatted field of information about this particular card, but without any blank lines.Let's take this information and store it in a text file. To keep things simple, the cards within the file are separated with a blank line, and the first line of each card will be the title.

For example, let's create a sample card file called 'cards.txt' and use it to store a list of our goals.

Write a book and become famous This is a long range goal. I need a good book idea first. And writing skills. Solve the problems of society This might take a little longer than expected. Take out the garbage It's stinking up the garage.

Let's begin with an Awk script to print out the titles of all the cards in the file. Here is the script called 'titles':

# titles - Print the titles of all the cards in the

# index card file.

BEGIN { RS = ""; FS = "\n" }

{ print $1 }

Here is a sample run:

[B:\] gawk -f titles cards.txt Write a book and become famous Solve the problems of society Take out the garbage [B:\]

Another useful script is one that can be used for searching the data file, ignoring uppercase and lowercase distinctions. The following script called 'search' will display the cards that contain the keyword 'write'.

# search - Print the index card that contains a string

BEGIN { RS = ""; FS = "\n"; IGNORECASE=1 }

/write/ { print $0, "\n" }

Here is a sample run:

[B:\] gawk -f search cards.txt Write a book and become famous This is a long range goal. I need a good book idea first. And writing skills. [B:\]

To search for other strings, edit the 'search' script and replace 'write' with another search keyword.

Sorting the cards based on the titles would also be a useful operation. Here is a script called 'sort' which reads the entire data file into and array and then uses the QuickSort algorithm to sort it:

# sort - Sort index card file by the card titles

BEGIN { RS = ""; FS = "\n" }

{ A[NR] = $0 }

END {

qsort(A, 1, NR)

for (i = 1; i <= NR; i++) {

print A[i]

if (i == NR) break

print ""

}

}

# QuickSort

# Source: "The AWK Programming Language", by Aho, et.al., p.161

function qsort(A, left, right, i, last) {

if (left >= right)

return

swap(A, left, left+int((right-left+1)*rand()))

last = left

for (i = left+1; i <= right; i++)

if (A[i] < A[left])

swap(A, ++last, i)

swap(A, left, last)

qsort(A, left, last-1)

qsort(A, last+1, right)

}

function swap(A, i, j, t) {

t = A[i]; A[i] = A[j]; A[j] = t

}

And here is a sample run:

[B:\] awk -f sort cards.txt > new.txt [B:\] ren cards.txt cards.bak [B:\] ren new.txt cards.txt [B:\] type cards.txt Solve the problems of society This might take a little longer than expected. Take out the garbage It's stinking up the garage. Write a book and become famous This is a long range goal. I need a good book idea first. And writing skills. [B:\]Note that we renamed our old data file to cards.bak, instead of deleting the file. It's always good to keep backups of old databases.

However, the 'sort' script had some trouble with large files because it reads in all the cards into an array in RAM. In my tests, the largest file I was able to sort was only about 100K.

Index cards can also be used for memorization. The title of the card can contain a question and the body of the card contains the answer that you want to memorize.

Let's write a program that randomly chooses a card from our 'cards.txt' file, displays its title, asks the user to press the 'Enter' key, and then displays the body of that card.

First, we need a text file which contains the questions and answers that we want to memorize. Let's name the file 'question.txt'. Note that the answer can contain multiple lines:

What is your name? My name is Sir Lancelot of Camelot. What is your quest? To seek the Holy Grail. What is your favorite color? Blue.

Here is the Awk script called 'memorize'. It will read the data file into an array, randomly shuffle the array, and then it will loop through the array and display each question and answer.

# memorize - randomly display an index card title, ask user to

# press return, then display the corresponding body of the card

BEGIN { RS=""; FS="\n" }

{ A[NR] = $0 }

END {

RS="\n"; FS=" "

shuffle(A, NR)

for (i = 1; i <= NR; i++) {

print "\nQUESTION: ", substr(A[i], 1, index(A[i], "\n")-1)

printf "\nPress return for the answer: "

getline < "-"

print "\nANSWER: "

print substr(A[i], index(A[i], "\n")+1)

if (i == NR) break

printf "\nPress return to continue, or 'q' to quit: "

getline < "-"

if ($1 == "q") break

}

}

# Shuffle the array

function shuffle(A, n, t) {

srand()

# Moses/Oakford shuffle algorithm

for (i = n; i > 1; i--) {

j = int((i-1) * rand()) + 1

t = A[j]; A[j] = A[i]; A[i] = t

}

}

Here is a sample run. The script will randomly choose cards until it either finishes going through all the cards, or until the user enters a 'q' to quit.

[B:\] gawk -f memorize question.txt QUESTION: What is your quest? Press return for the answer: ANSWER: To seek the Holy Grail. Press return to continue, or 'q' to quit: QUESTION: What is your favorite color? Press return for the answer: ANSWER: Blue. Press return to continue, or 'q' to quit: QUESTION: What is your name? Press return for the answer: ANSWER: My name is Sir Lancelot of Camelot. [B:\] gawk -f memorize question.txt QUESTION: What is your favorite color? Press return for the answer: ANSWER: Blue. Press return to continue, or 'q' to quit: q [B:\]

The databases above used a simple 'index card' analogy. That data model works fine for simple lists with free form data, but there are also cases where we need to manage records with specialized data fields.

Let's create a data file and some scripts for an 'address book' database. Our data file will be a text file where every line is one record. Within a line of the file, the data will be separated into fields.

When choosing a delimiter for our fields, we need to make sure that it won't appear accidentally within a field itself. For example, an address book has fields like name, company name, address, etc., and in this case, each of those fields can contain spaces within them (e.g. "ACME Mail Order Company"). Therefore, we can't use a space to separate the fields of the line.

Instead, let's use commas to separate the fields, and we'll need a rule that commas cannot appear within a field.

Here is a sample data file called 'address.txt':

John Robinson,Koren Inc.,978 4th Ave,Boston,MA 01760,617-696-0987 Phyllis Chapman,GVE Corp.,34 Sea Drive,Amesbury,MA 01881,781-879-0900Here is the script called 'labels' which will print all the data and format it like mailing labels:

# labels - Format the addresses for printing labels

# Source: blocklist.awk from "Sed & Awk", by Dale Dougherty, p.148

BEGIN { FS = "," }

{

print "" # blank line

print $1 # name

print $2 # company

print $3 # street

print $4, $5 # city, state zip

}

This is the sample run:

[B:\] gawk -f labels address.txt John Robinson Koren Inc. 978 4th Ave Boston MA 01760 Phyllis Chapman GVE Corp. 34 Sea Drive Amesbury MA 01881 [B:\]

It may also be useful to extract just the phone numbers from our data file. Here is the script called 'phones' which will extract only the names and phone numbers from the data file:

# phones

# Source: phonelist.awk, from "Sed & Awk", by Dale Dougherty, p.148

BEGIN { FS="," }

{ print $1 ", " $6 }

Here is a sample run:

[B:\] gawk -f phones address.txt John Robinson, 617-696-0987 Phyllis Chapman, 781-879-0900 [B:\]We'll also need a script to search our data file for a name. Here is a script called 'searchad' with will search for the string 'robinson':

# searchad - Return the record that matches a string

BEGIN { FS = ","; IGNORECASE=1 }

/robinson/ {

print "" # blank line

print $1 # name

print $2 # company

print $3 # street

print $4, $5 # city, state zip

}

Here is a sample run:

[B:\] gawk -f searchad address.txt John Robinson Koren Inc. 978 4th Ave Boston MA 01760 [B:\]

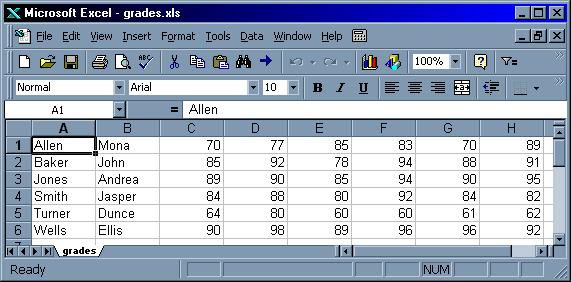

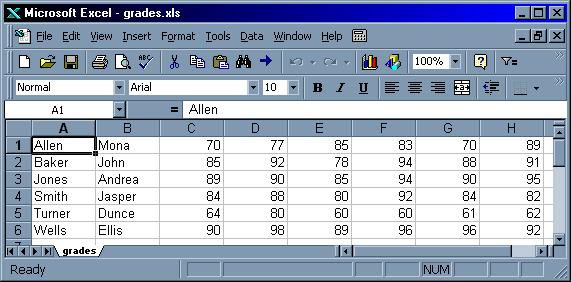

Awk can also be used for mathematical computation of fields. Let's demonstrate this with a data file called 'grades.txt' that contains grades of students.

Allen Mona 70 77 85 83 70 89 Baker John 85 92 78 94 88 91 Jones Andrea 89 90 85 94 90 95 Smith Jasper 84 88 80 92 84 82 Turner Dunce 64 80 60 60 61 62 Wells Ellis 90 98 89 96 96 92

Here is a longer script that will take all the grades, average them equally, and compute the final average and the final grade for each student. At the end, it will compute some statistics about the entire class. Here is the script called 'grades'.

# grades -- average student grades and determine

# letter grade as well as class averages

# Source: "Sed & Awk", by Dale Dougherty, p.192

# set output field separator to tab.

BEGIN { OFS = "\t" }

# action applied to all input lines

{

# add up the grades

total = 0

for (i = 3; i <= NF; ++i)

total += $i

# calculate average

avg = total / (NF - 2)

# assign student's average to element of array

class_avg[NR] = avg

# determine letter grade

if (avg >= 90) grade="A"

else if (avg >= 80) grade="B"

else if (avg >= 70) grade="C"

else if (avg >= 60) grade="D"

else grade="F"

# increment counter for letter grade array

++class_grade[grade]

# print student name, average, and letter grade

print $1 " " $2, avg, grade

}

# print out class statistics

END {

# calculate class average

for (x = 1; x <= NR; x++)

class_avg_total += class_avg[x]

class_average = class_avg_total / NR

# determine how many above/below average

for (x = 1; x <= NR; x++)

if (class_avg[x] >= class_average)

++above_average

else

++below_average

# print results

print ""

print "Class Average: ", class_average

print "At or Above Average: ", above_average

print "Below Average: ", below_average

# print number of students per letter grade

for (letter_grade in class_grade)

print letter_grade ":", class_grade[letter_grade]

}

Here is a sample run:

[B:\] gawk -f grades grades.txt Allen Mona 79 C Baker John 88 B Jones Andrea 90.5 A Smith Jasper 85 B Turner Dunce 64.5 D Wells Ellis 93.5 A Class Average: 83.4167 At or Above Average: 4 Below Average: 2 A: 2 B: 2 C: 1 D: 1 [B:\]

Another useful script is the following program that computes a histogram of the grades. It is hardcoded to only read the third column ($3), but you can edit it and change it to read any of the columns in the input file. Here is the script called 'histo':

# histogram

# Source: "The AWK Programming Language", by Aho, et.al., p.70

{ x[int($3/10)]++ } # use the third column of input data

END {

for (i = 0; i < 10; i++)

printf(" %2d - %2d: %3d %s\n",

10*i, 10*i+9, x[i], rep(x[i],"*"))

printf("100: %3d %s\n", x[10], rep(x[10],"*"))

}

function rep(n, s, t) { # return string of n s's

while (n--> 0)

t = t s

return t

}

And here is the sample run:

[B:\] gawk -f histo grades.txt 0 - 9: 0 10 - 19: 0 20 - 29: 0 30 - 39: 0 40 - 49: 0 50 - 59: 0 60 - 69: 1 * 70 - 79: 1 * 80 - 89: 3 *** 90 - 99: 1 * 100: 0 [B:\]

The output shows that there were six grades, and most of them were in the 80-89 range.

This program takes a data file which lists your checkbook entries and your deposits, and calculates the totals.

Here is what a sample input file called 'checks.txt' looks like:

check 1021 to Champagne Unlimited amount 123.10 date 1/1/87 deposit amount 500.00 date 1/1/87 check 1022 date 1/2/87 amount 45.10 to Getwell Drug Store tax medical check 1023 amount 125.00 to International Travel date 1/3/87 check 1024 amount 50.00 to Carnegie Hall date 1/3/87 tax charitable contribution check 1025 to American Express amount 75.75 date 1/5/87

Here is the script called 'check' which will calculate the totals:

# check - print total deposits and checks

# Source: "The AWK Programming Language", by Aho, et.al., p.87

BEGIN { RS=""; FS="\n" }

/(^|\n)deposit/ { deposits += field("amount"); next }

/(^|\n)check/ { checks += field("amount"); next }

END { printf("Deposits: $%.2f, Checks: $%.2f\n",

deposits, checks)

}

function field(name, i, f) {

for (i = 1; i <= NF; i++) {

split($i, f, "\t")

if (f[1] == name)

return f[2]

}

printf("Error: no field %s in record\n%s\n", name, $0)

}

And this is a sample run:

[B:\] gawk -f check checks.txt Deposits: $500.00, Checks: $418.95 [B:\]

The script took six seconds to run.

Awk works well with data files that are stored in text files. Awk assumes that the data file is organized into records, within each record the data is divided into fields, and there are unique characters in the file that are used as the field separators and record separators.

By default, Awk assumes that newline characters are the record separators and whitespace characters (spaces and tabs) are the field separators. It is also possible to redefine the field separators to other characters, like a comma or a tab character, which means that Awk can process the commonly used "comma separated" and "tab separated" format for data files.

But note that if a file uses newline characters as record separators, it means that a newline cannot appear within a field. For example, a data file file with one record per line cannot contain a text field (e.g. a "notes" field) that contains free form text with newline characters within it. That would confuse Awk unless we added special code to handle that notes field.

The same restrictions apply to the field separators. If a file is defined to be comma separated, it means that no field is allowed to contain comma characters within it (e.g. a Name field that contains "Alvarado, Victor") because Awk would parse that as two fields, not one.

That is why tab separated files tend to be used more often. That way, the fields are allowed to contain spaces and commas.

Another way to format data for use by Awk is to use the "multiline" format, which is what we used for our index card databases above. Awk will treat each line as a field, and a blank line is the record separator.

To export data to Excel, all we need to do is to convert the data file into tab-delimited format, and store it in a text file with a *.xls extension. When that file is opened in Microsoft Windows, Excel will open it automatically as if it were a spreadsheet.

As an example, let's export our grades.txt file to Excel. Here is our 'grades.txt' file:

Allen Mona 70 77 85 83 70 89 Baker John 85 92 78 94 88 91 Jones Andrea 89 90 85 94 90 95 Smith Jasper 84 88 80 92 84 82 Turner Dunce 64 80 60 60 61 62 Wells Ellis 90 98 89 96 96 92

The file uses spaces as the field separator, so we'll need a script that will convert the field separators into tabs. Here is a script called 'conv2xls':

# conv2xls - Convert a data file into tab-separated format

BEGIN {

IFS=" " # input field separator is a space

OFS="\t" # output field separator is a tab

}

{ print $1, $2, $3, $4, $5, $6, $7, $8 }

And here is the sample run, where we store the tab-delimited output into a text file called grades.xls:

[B:\] gawk -f conv2xls grades.txt > grades.xls [B:\]Here is the contents of the 'grades.xls' text file:

Allen Mona 70 77 85 83 70 89 Baker John 85 92 78 94 88 91 Jones Andrea 89 90 85 94 90 95 Smith Jasper 84 88 80 92 84 82 Turner Dunce 64 80 60 60 61 62 Wells Ellis 90 98 89 96 96 92

We can then copy the grades.xls text file to a Windows PC, double-click on it, and Excel will open it as if it were a spreadsheet:

You can then do a "Save As" in Excel to save it as the regular Excel binary format.

To export our data to a web page, we will need a script that will input our data file and generate HTML.

Let's start with our 'grades.txt' data file:

Allen Mona 70 77 85 83 70 89 Baker John 85 92 78 94 88 91 Jones Andrea 89 90 85 94 90 95 Smith Jasper 84 88 80 92 84 82 Turner Dunce 64 80 60 60 61 62 Wells Ellis 90 98 89 96 96 92

Here is a script called 'html' that will do the conversion. Note that the data will appear as rows of a table in HTML.

# html - Convert a data file into an HTML web page with a table

BEGIN {

print "<HTML><HEAD><TITLE>Grades Database</TITLE></HEAD>"

print "<BODY BGOLOR=\"#ffffff\">"

print "<CENTER><H1>Grades Database</H1></CENTER>"

print "<HR noshade size=4 width=75%>"

print "<P><CENTER><TABLE BORDER>"

printf "<TR><TH>Last<TH>First"

print "<TH>G1<TH>G2<TH>G3<TH>G4<TH>G5<TH>G6"

}

{ # Print the data in table rows

printf "<TR><TD>" $1 "<TD>" $2

printf "<TD>" $3 "<TD>" $4 "<TD>" $5

print "<TD>" $6 "<TD>" $7 "<TD>" $8

}

END {

print "</TABLE></CENTER><P>"

print "<HR noshade size=4 width=75%>"

print "</BODY></HTML>"

}

Here is the sample run.

The output will be placed in a file called 'grades.htm'.

[B:\] gawk -f html grades.txt > grades.htm [B:\]This is what the resulting 'grades.htm' file looks like:

<HTML><HEAD><TITLE>Grades Database</TITLE></HEAD> <BODY BGOLOR="#ffffff"> <CENTER><H1>Grades Database</H1></CENTER> <HR noshade size=4 width=75%> <P><CENTER><TABLE BORDER> <TR><TH>Last<TH>First<TH>G1<TH>G2<TH>G3<TH>G4<TH>G5<TH>G6 <TR><TD>Allen<TD>Mona<TD>70<TD>77<TD>85<TD>83<TD>70<TD>89 <TR><TD>Baker<TD>John<TD>85<TD>92<TD>78<TD>94<TD>88<TD>91 <TR><TD>Jones<TD>Andrea<TD>89<TD>90<TD>85<TD>94<TD>90<TD>95 <TR><TD>Smith<TD>Jasper<TD>84<TD>88<TD>80<TD>92<TD>84<TD>82 <TR><TD>Turner<TD>Dunce<TD>64<TD>80<TD>60<TD>60<TD>61<TD>62 <TR><TD>Wells<TD>Ellis<TD>90<TD>98<TD>89<TD>96<TD>96<TD>92 </TABLE></CENTER><P> <HR noshade size=4 width=75%> </BODY></HTML>

And here is a link to the grades.html file so you can see what the web page looks like in your browser.

As you can see, storing data as text files gives you a lot of flexibility in manipulating the data and exporting it to other formats.